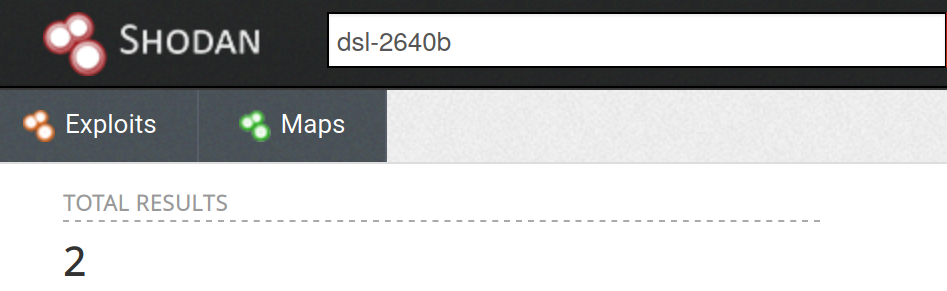

We identified several vulnerabilities in the D-Link DSL-2640B DSL gateway which will likely not be fixed as the device is EoL (more details will come soon). A vulnerability identified in an EoL device typically has a guaranteed, infinite lifetime. Basically a NO-day. Although Shodan only reports only two active devices, we like to stress that the impact of these vulnerabilities should not be neglected.

The DNSChanger malware has been updated in 2018 to target the DSL-2640B. The attacker's efforts would be hard to explain with just Shodan's figures. An analysis performed by Bad Packets using data from a different source, identified a much larger device population, excessing 14,000 active devices. The stark difference between device population numbers questions our ability to correctly assess relevance, scale and impact of EoL devices.

The device population size may be surprising for a device that is EoL for more than 7 years. Taking control of such a large device population allows for attacks at scale, such as contributing significant bandwidth in a DDoS attacks. The data directly challenges the perceived relevance of EoL devices in general.

Important: The information described in this blog post was also discussed at NULLCON 2020 for which the slides can be downloaded here.

End-of-Life?

End-of-Life refers to the life-cycle stage of a device, where no support is provided anymore. This typically includes security updates for newly identified vulnerabilities.

One may expect that the device population rapidly declines once a device becomes EoL. We are not aware of any research that explores an EoL device population evolutions and time it takes before the device disappear from the Internet. It is safe to assume that the lifetime of some devices (e.g. routers, modems, TVs, etc.) may be significantly longer than expected.

Devices that are EoL are rarely considered interesting for security research as:

- the manufacturer is not interested and vulnerabilities will not be fixed

- exploitation is not interesting as it is simply too easy

- the device is out of scope of any bug bounty program

- the device population will likely go to zero (at some point)

However, any vulnerability will have an almost guaranteed, infinite life. Any attacker will be able to exploit such a vulnerability, until the last device is disconnected from the Internet.

D-Link DSL-2640B

The D-Link DSL-2640B is a DSL gateway first released in 2007 and sold in several countries. The US version has been in EoL since 2013. No information is known to us about the devices sold in other countries.

This device may easily look like an uninteresting target. Until recently, only one CVE was a available for a XSS vulnerability, which was reported in 2012. It's not surprising that the research community is uninterested as Shodan only reports 2 available devices.

This may indicate that this device has disappeared from the Internet and that any identified vulnerability will be practically irrelevant.

We have reasons to believe that real attackers do not share the same view…

Learning from malware

A DNSChanger malware campaign, which took place between December 2018 and April 2019, hijacked network traffic of users by reconfiguring remotely the DNS servers of several vulnerable consumer routers. Bad Packets analyzed this DNS hijacking campaign and identified 7 distinct attack waves targeting different routers, sharing their results in a nice blog post.

The DNSChanger malware was already active in 2016. At that time it was not yet targeting the D-Link DSL-2640B. In 2017, an exploit got posted to exploit-db.com that allows unauthenticated modification of the device's DNS server settings. This vulnerability is used by the DNSChanger malware during its 2018-2019 campaign.

In a nutshell, the DNSChanger malware was intentionally updated to support a target, which, according to Shodan, had practically disappeared from the Internet…

WHY!?

Lies, damned lies, and statistics

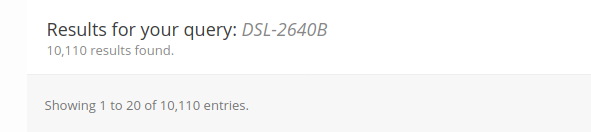

An important piece of information in the blog post by Bad Packets is their estimation of affected devices. Instead of using Shodan for their estimate, they used data provided by BinaryEdge. Long story short, they concluded that the device population of the DSL-2640B is a whopping amount of 14,327!

BinaryEdge's count exceeds Shodan's results by 4 orders of magnitude (!).

One may wonder whether such results are accurate and which of the two is the most accurate. This is a valid question and it would definitely be interesting to understand the reason for this significant difference. We would love to hear if anybody knows more about his.

Just to be sure, we performed a few sanity checks on the BinaryEdge data and, based on our limited capabilities (i.e. we cannot simply exploit these devices to check), we concluded that the count may be realistic.

NOTE:

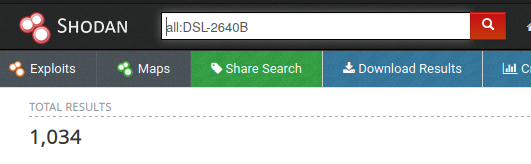

For consistency reasons, the same search string has been used for both search engines, with the intent to show of how strikingly different figures may be obtained.

More tailored queries may yield different numbers on each of the search engines. For instance, we have been pointed to our best Shodan query so far, which yields slightly above 1k devices. This is still one order of magnitude different from BinaryEdge.

Impact

if we assume that the BinaryEdge data is realistic, we need to reconsider the relevance of vulnerabilities affecting the D-Link DSL-2640B.

Firstly, it's interesting that even after 7 (!) years of EoL 10,000 device are still reachable over the Internet. This directly challenges the assumption that EoL devices's population declines to extinction in a considerable amount of time. In other words, if the numbers are correct, it's clear that a rapid disappearance of EoL devices cannot be safely assumed and it fully justifies the malware's choice to include the device in its list of targets.

Secondly, the relevance of exploits affecting EoL devices, with a guaranteed infinite lifetime, increases drastically when such devices do not actually disappear. This directly challenges the assumption that exploits affecting EoL devices are useless as the population count rapidly approaches zero. Exploits are definitely not useless when they affect 10,000+ Internet connected devices.

Lastly, attackers are always interested in exploiting large populations of Internet connected devices, also when old, slow and EoL. The DSL-2640B has an upstream bandwidth of 3.5 Mbps and therefore the aggregate bandwidth of the 10,000 devices is 35 Gbps. This would be a significant contribution in DDoS attacks, especially if further amplified via various techniques like DNS Amplification, NTP Amplification or TCP Reflection.

This made us wonder… what is the actual value of an exploit for an EoL device?

We have not been able to find solid data on the value of exploits for EoL devices. In March of this year a new vulnerability for the DSL-2640B was released affecting a specific firmware version. This vulnerability enables an attacker to perform an unauthenticated firmware update. VulDB provides an estimated value between 5,000 USD and and 25,000 USD. We wonder if this estimate takes the device population size into account. Nonetheless, it should be evident that a larger population would make the exploit more valuable.

Final thoughts

More and more devices will become EoL each year. We also know that users will keep on using them, regardless of security recommendations. This situation is not easy to address, for instance, kill switches implemented by the manufacturers are likely undesired or even illegal. A possible measure may inform users of the EoL status of the device and its risk, potentially fueling device replacement/disconnection.

We believe that it is also fundamental to provide adequate methods for mapping the device population of EoL devices. Services like Shodan and BinaryEdge are definitely useful, but we have shown how they can provide greatly conflicting data, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions.

Someone may also suggest that ISPs (or Manufacturers) should be responsible for tracking, and reporting, Internet connected devices. Protocols like TR-069 are actually used by ISPs already and may facilitate this purpose as well.

Regardless of the solution, we believe that it takes more than just technical measures to effectively address the threat posed by EoL devices to the Internet ecosystem.

We would love to hear your thoughts: @raelizecom.